Unlearning White Supremacy discussion group: reflections on the “free Tibet syndrome”

After an overt act of violence, well-intentioned folks often reach out to offer support to affected groups. Many of these folks are often white settlers, and they offer support in many different ways; for example, many folks will take to social media to tweet a new solidarity hashtag or change a cover photo to incorporate a new symbolic filter. Sometimes acts of support even manifest as monetary donations to an organization or a solidarity march/protest.

The anti-Islam violence in Quebec City and the new US president’s anti-Islam and anti-immigration executive orders seeking to ban Muslims have both evoked strong responses from many communities, including folks in Victoria and students at Uvic. There have been waves of solidarity posts on social media, kind messages and flowers dropped off at local mosques, and vigils to commemorate those affected by the highly publicized attacks.

In many ways, it is not surprising that both these acts of white supremacist violence would be brought up at AVP’s second Unlearning White Supremacy discussion group. In fact, it would be inappropriate to not name them as they were both acts of white supremacy.

However, one thing that came up in our discussion was how these well-intended conversations and actions often result in a more insidious effect.

Distancing violence and the move to innocence

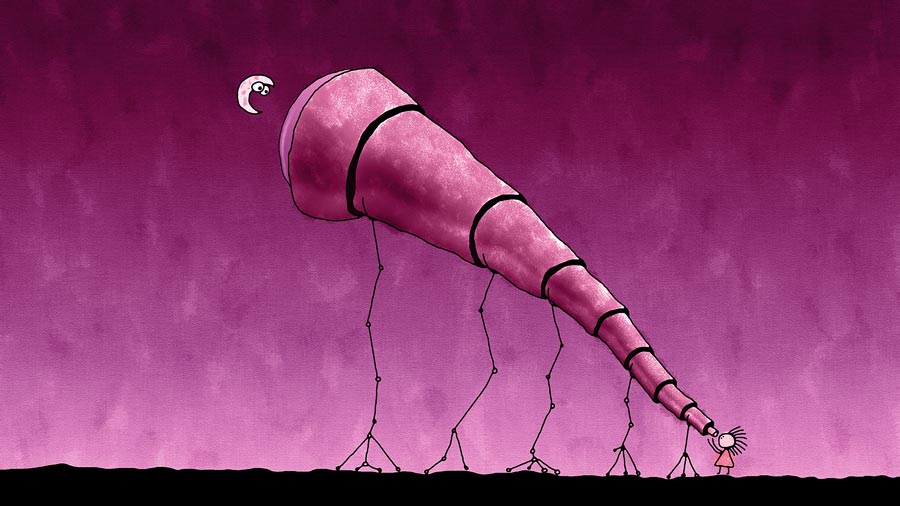

By directing our gaze towards a faraway act of violence, white settlers often implicitly create a sense of distance from said violence.

In other words, by focusing my attention on the violence in Québec City and the US, I run the risk of subtly establishing a boundary that separates myself from a newly formed Other, who becomes defined by explicit acts of colonial and white supremacist violence.1

Such a process of distancing/Othering is often referred to as the “Free Tibet syndrome”. By defining violence as ‘out there’, folks frame their own lives and communities as innocent and good. This ‘move to innocence’ is problematic because it enables groups to ignore the local struggles and violence occurring within their own communities and how they may be contributing to these struggles and violence.

Everyday we all participate in a society that is defined by colonial white supremacist violence.

I am only able to live here due to the displacement of LEKWUNGEN and W̱SÁNEĆ peoples. I am directly benefiting from the colonial and white supremacist systems that framed and continue to frame Indigenous peoples as inferior to others.

We all engage in settler colonialism, and we all engage in white supremacy culture.

Yet, when we white settler folks distance ourselves from acts of violence, we erase and invisiblize these facts, which makes it easier for us to believe that we don’t need to change. We create boundaries that allow us to assume that such violence doesn’t occur in our communities.

The “not here” attitude that comes with the Free Tibet Syndrome lets us continue with business as usual. Such an either/or way of thinking reinforces white supremacy culture because it absolves us from taking accountability for our own actions.2

This is not to say that acts of solidarity are unimportant. Such acts offer support to those who have experienced violence and/or are feeling unsafe, and they can also lead to collective action that challenges systems of power that produce and reproduce such violence.

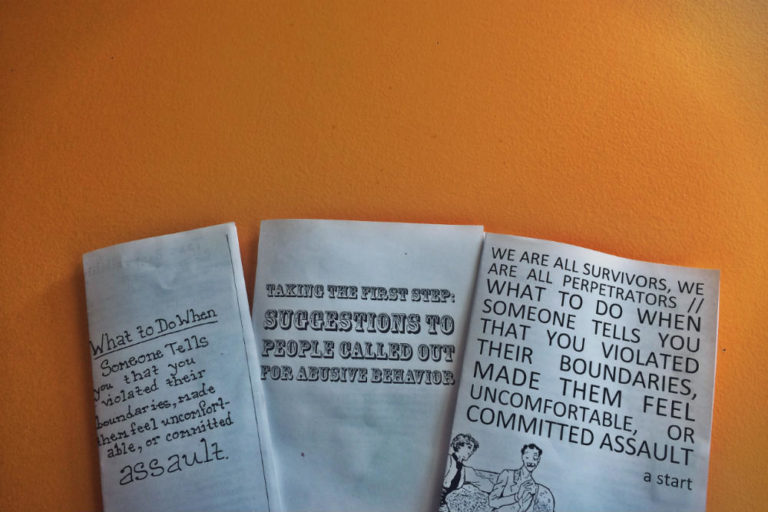

But it is important that we continue to reflect on our own actions and behaviours. It is important that we self-implicate ourselves and critically reflect on the ways we contribute to and benefit from colonization, white supremacy, and other systems of power. Reflecting on our responses to violence perpetrated elsewhere or by others can help us prevent the perpetuation of the mentalities that made such acts possible in the first place.

Furthermore, it’s not just about not being violent; it’s about how we work with one another to establish communities that emphasize responsibility and care. What are white folks doing right now in communities to let Muslims know they are appreciated? What are settlers doing to centre those Indigenous voices that have been marginalized through processes of colonization?

We need to resist the impulse to border off ourselves from violence by framing it as elsewhere simply to keep the sense of comfort (and privilege) that comes with thinking of ourselves as inherently good people. None of us are perfect.

Instead, we should open ourselves up to the feelings of discomfort that come with knowing that we are imperfect and that we are implicated. Only after realizing how we contribute to and benefit from different systems of power can white settler folks begin to unlearn and challenge these systems.

- See for example Othering and Orientalism. ↩

- See also “The Race to Innocence” (PDF) by Sherene Razack and Mary Louise Fellows. ↩